Series 08: From pure measure to emotion, 1992-1993

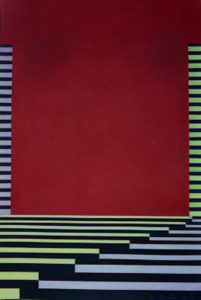

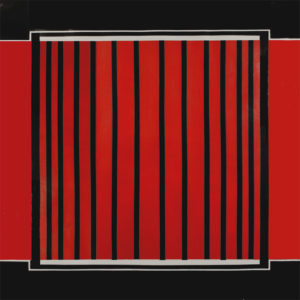

- 08-01

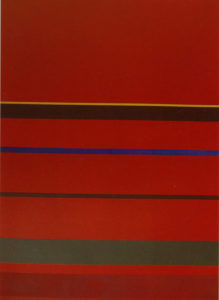

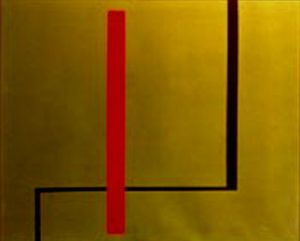

- 08-02

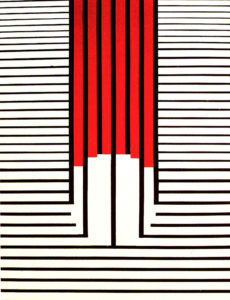

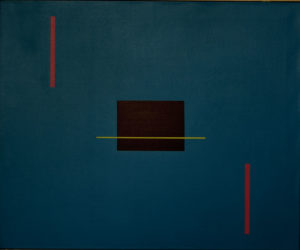

- 08-03

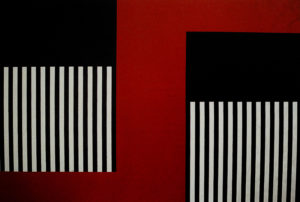

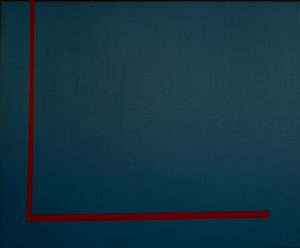

- 08-04

- 08-05

- 08-06

- 08-07

- 08-08

- 08-09

- 08-10

- 08-11

- 08-12

- 08-13

Series 08: From pure measure to emotion, 1992-1993

Contents of the exhibition at Anselmo Álvarez, Madrid: From pure measure to emotion

I. Mondrian, beginning and end.

Throughout its history, attitudes towards art have varied immensely, as have the uses of painting in particular.

Even so, two orientations have most enhanced the human race. These two are the most necessary too, if we believe we belong in a world in constant movement and evolution.

A.- The one that expresses such a world.

B.- The one that is concerned with learning it to improve it. And, while being aware that, in artists genuinely committed to art, both attitudes eventually form part of the whole through their constant connection, I still think it worthwhile to apprehend and meditate on the difference between the two, particularly as I consider means and ends to be of vital importance when we talk about art.

Mondrian said: “Seeing –as objectively as possible– is the principal ambition of all plastic art. If objective vision were possible, it would give us a true image of reality.”

As a professional painter, Giotto, like Cezanne, magnified the daily struggle to better understand his art and craft and pass on to us snippets of knowledge that enhance our sensory perception.

In their respective oeuvres, two superlatively gifted artists, Velázquez and Raphael, left us genuine messages of realities that, precisely because they are subjective, contain more essentiality.

Taken as a whole, the plastic arts of the 20th century offer a huge range of explorations into the most individualized being. Styles are means: they become tools for inner knowledge, consciously used to that end. The anxiety produced by the perception of far-reaching change actually blends with the feeling that painting is dead; when what really happens is that, as in any revolution, conscious knowledge of its reconstructive power actually increases.

Placing Mondrian in this context, we see that his intuition pushes him to eliminate everything that is not essential to pure plastic art; for instance: theme, which might distract the artist from the exploration and discovery of the pure plastic elements (dot, line, plane and color).

Likewise, he renounces expression in an attitude of generous responsibility and for the sake of a direct relation between means and ends: painting and knowledge of the world.

Art and science unite

Throughout the century, painters made some magnificent progress in this regard; but Mondrian, or at least that’s how I see it, was perhaps the furthest out on the edge between the concepts of contemporaneousness and future.

His renunciations of theme and expression, his respect for and acceptance of the limits of the support and of the pure plastic elements make him the supreme maestro of all painters interested in using paint in a particular way, one directly associated with the movement of the world; with life in it.

II. The quantum lens and the concept of division Looked at globally, human pain is so excessive that we are all forced to some extent, individually or collectively, to make multiple divisions so as not to feel it.

Today’s most topical philosophy, in the works of Emmanuel Levinas and Georges Balandier, seeks to comprehend

and explain the utter rejection of “the other”. At times, a tiny difference, no matter how small, is intolerable which makes it“more economical to separate.”

In plastic terms, and, if we want to be objective about the contemporary situation, from the point of view of a revolution in favor of equal rights for all, admitting also the potential differences there might be between us, without making our fellow creatures pay for it, in the established scale of values (division) we are forced to acquire a greater

potentiality, achieved through discovering and assimilating:

– Concept of Void. Already met with, as a fl ight from reality.

– Concept of Tension. Produced by repressions of plastic energy.

– Concept of Division. The multiple “divisions” we are capable of making to avoid pain.

Bernard D’Espagnat deals with this theme in his book In search of the real: A physicist’s view, through the concept of “non-separativity”. Contemporary music subjects time to minute examination; in contemporary ballet, one of today’s most prestigious choreographers, William Forsythe, uses the bodies of his dancers to act out on stage a detailed, thorough-going movement of all bodily matter. Knowledge of every millimeter of the body and its functions is the basis of dance. The gestures, the expressions, the form or size of the dancers, are not essential.

Their individual features and characteristics are not important. Knowledge of the full potential of the body puts them in a position to use it, in a perfect, distinctive space-time relation.

It’s like that too with plastic art. We’ve got to know how to measure minutely each dot in the plane, ensuring its direction is exact and its occupation correct.

The construction of the plane and its relation with the plane-support, and the multiple modifi cations that affect them, creators of meanings.

The dimensions of color that, together with the measurement of the selected planes, unify and harmonize the composition.

We use the knowledge of pure plastic elements to construct an image that produces an emotion, which in turn provokes a sensory discovery or experience.

In dance, Antonio Canales constructs rhythms and symbols capable of producing multiple emotions; he uses technique to relate to the public and produce the emotive link.

And that, in my commitment to painting today, is exactly what I’m up to now.

Inés Medina. October 93